Understanding Computer Architecture: How Your Computer Processes Information

Have you ever wondered what happens behind the scenes when you click on an application or run a program? Your computer orchestrates a complex dance between multiple components, each playing a crucial role in executing your commands. Think of it like a highly efficient office where different departments work together seamlessly to get things done. Let's break down the fundamental architecture that makes modern computing possible, and I promise to keep it simple and relatable.

The Language of Computers: Binary and Data Units

Before we dive into the hardware components, we need to understand how computers actually "think." Unlike humans who use words and decimal numbers, computers speak an entirely different language: binary. This might sound complicated, but it's actually beautifully simple.

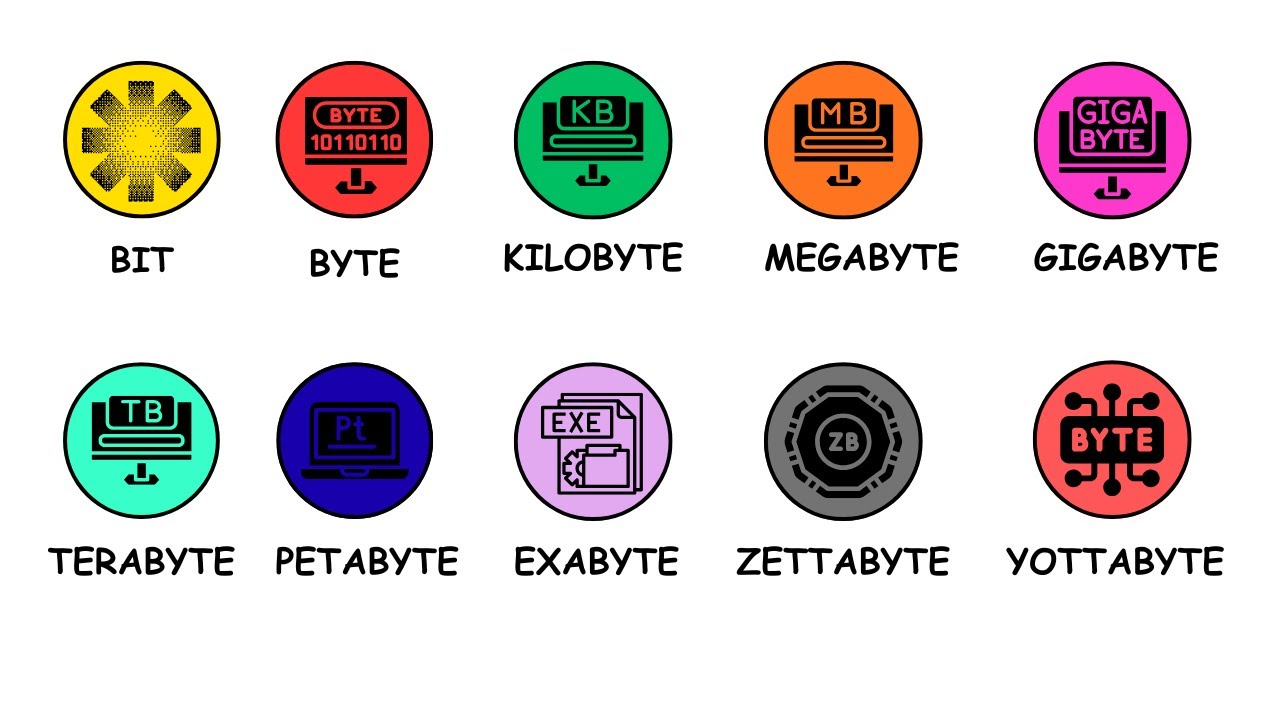

At its core, your computer understands only two states: on or off, yes or no, 0 or 1. These are called "bits," and they're the absolute smallest unit of information a computer can process. Imagine a light switch that can only be flipped up or down. That's essentially what a bit is.

Now, one bit alone can't do much. It can only represent two possibilities. But when you combine eight bits together, you get what's called a "byte." A single byte can represent 256 different combinations (that's 2 to the power of 8), which is enough to represent any letter, number, or symbol you might type on your keyboard. For example, the letter "A" is represented by a specific pattern of eight bits, and the number "7" has its own unique eight-bit pattern.

But modern computers handle much more than just individual characters. We need bigger units to measure all the data we work with:

- Kilobyte (KB): About 1,000 bytes. This could store a few paragraphs of text.

- Megabyte (MB): About 1,000 kilobytes. Think of a high-quality photo or a minute of MP3 music.

- Gigabyte (GB): About 1,000 megabytes. This is where we start measuring things like movies or large applications.

- Terabyte (TB): About 1,000 gigabytes. This is massive storage, enough for thousands of movies or hundreds of thousands of photos.

These units help us talk about storage and memory in meaningful ways. When someone says their phone has 128GB of storage, you now know that's roughly 128 billion bytes, or enough space for tens of thousands of photos.

Disk Storage: Your Computer's Long-Term Memory

Let's start with where everything in your computer actually lives permanently: disk storage. If your computer were a house, disk storage would be like all the closets, cabinets, and storage rooms where you keep your belongings safe for the long term.

Disk storage is where your operating system (like Windows or macOS) lives, along with all your applications, documents, photos, videos, and music. Everything you've ever saved on your computer is sitting somewhere on this disk. There are two main types of disk storage, and understanding the difference between them is important.

Hard Disk Drives (HDD): These are the traditional spinning disks that have been around for decades. Inside an HDD, there are actual physical disks (called platters) that spin at high speeds, and a tiny arm with a read/write head moves across these disks to access data. It's a bit like an old record player, but much more sophisticated. HDDs are generally cheaper and offer large storage capacities, but because they have moving parts, they're slower and more prone to damage if dropped.

Solid State Drives (SSD): These are the modern alternative, with no moving parts at all. Instead, they use flash memory chips (similar to what's in a USB thumb drive, but much faster and more reliable). Because there's nothing that needs to physically move to access data, SSDs are dramatically faster than HDDs.

The most important characteristic of disk storage, whether HDD or SSD, is that it's non-volatile. This is a fancy term that simply means the data stays put even when the power is off. You can shut down your computer, unplug it, leave it off for months, and when you turn it back on, all your files will still be there, exactly as you left them. This is fundamentally different from other types of memory we'll discuss shortly.

Storage Capacity: Modern disk storage is quite generous. Consumer laptops and desktops typically come with anywhere from 256GB to 2TB of storage. If you're a casual user who mainly browses the web, works with documents, and stores a moderate photo collection, 256GB to 512GB is usually plenty. Power users who edit videos, store large game libraries, or maintain extensive photo collections might need 1TB or more.

Speed Differences Matter: Here's where SSDs really prove their worth. An HDD typically reads data at speeds of 80 to 160 megabytes per second. That might sound fast, but modern SSDs can read data at speeds ranging from 500 MB per second all the way up to 3,500 MB per second for high-end models. Some cutting-edge SSDs can even exceed 7,000 MB per second.

What does this mean in practical terms? If you're booting up your computer, an HDD might take 30 to 60 seconds to load everything, while an SSD can have you up and running in 10 to 15 seconds. Opening a large application like Photoshop might take 30 seconds on an HDD but only 5 seconds on an SSD. Over the course of a day's work, these seconds add up to minutes, making your entire computing experience feel much snappier and more responsive.

This speed difference is why you'll often hear tech enthusiasts say that upgrading to an SSD is the single best improvement you can make to an older computer. Even a modest SSD can make a five-year-old computer feel fast and responsive again.

RAM: The Active Workspace

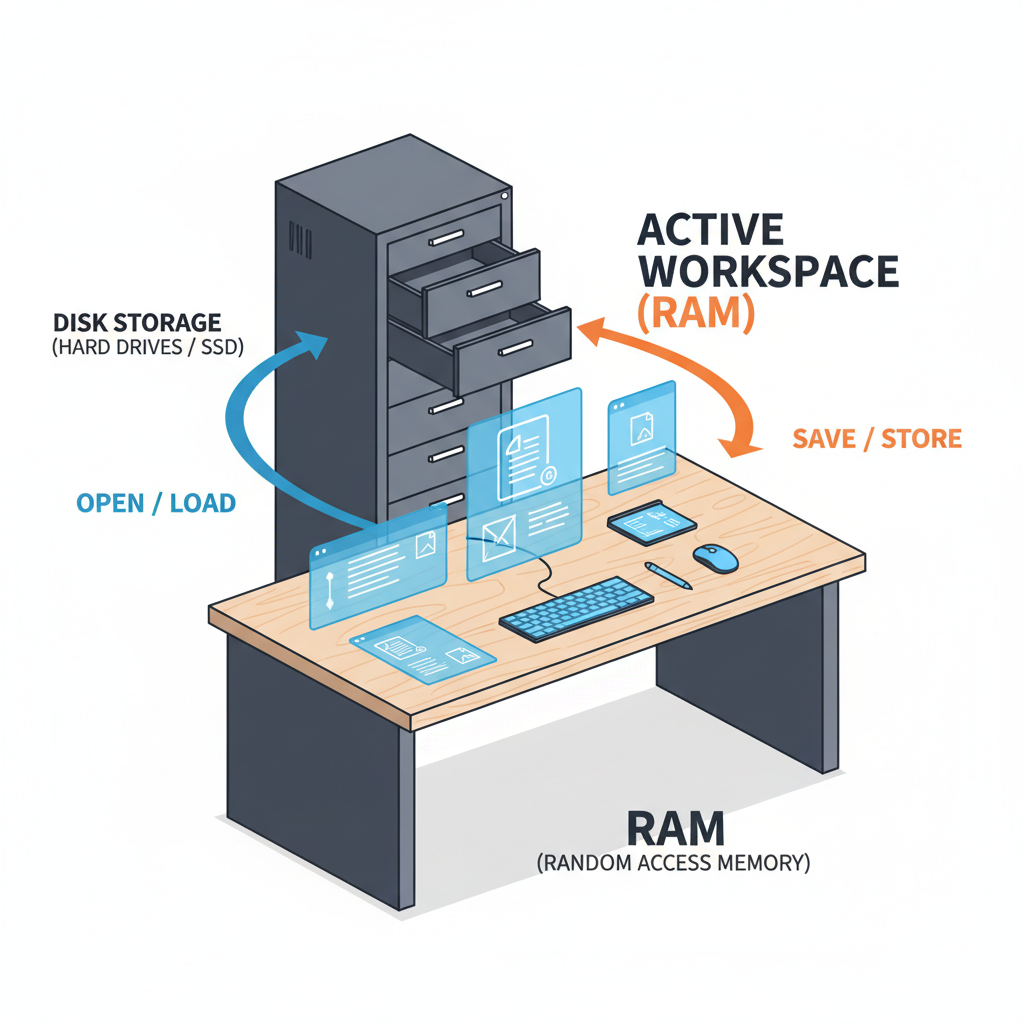

Now let's talk about Random Access Memory, or RAM. If disk storage is your computer's long-term filing cabinet, then RAM is like your desk workspace. It's where your computer keeps everything it's actively working on right now.

Here's how it works in practice: when you double-click on an application icon, your computer doesn't run that program directly from the disk. Instead, it copies the program from disk storage into RAM. Why? Because RAM is much, much faster than even the fastest SSD. The CPU can access data from RAM almost instantaneously, allowing programs to run smoothly.

Think about what happens when you're multitasking. You might have a web browser open with ten tabs, a word processor working on a document, a music player streaming your favorite playlist, and a messaging app keeping you connected with friends. Each of these programs is loaded into RAM, along with all the data they're currently using. The browser tabs are stored in RAM, the document you're editing is in RAM, the music buffer is in RAM, and your recent messages are in RAM.

Variables and Active Data: When a program runs, it creates variables and data structures that need to be stored somewhere quickly accessible. For example, if you're using a photo editing app and you apply a filter to an image, the program needs to store both the original image and the modified version somewhere while you decide whether you like the change. That temporary storage happens in RAM. The program might also store intermediate calculations, the history of your edits (for the undo function), and various other pieces of information that make the app work smoothly.

The Volatile Nature: Here's the critical thing to understand about RAM: it's volatile memory. Unlike disk storage, RAM needs constant electrical power to maintain its contents. The moment your computer loses power, either through a shutdown, restart, or unexpected power loss, everything in RAM disappears instantly.

This is why you lose unsaved work when your computer crashes. That document you were typing? It was in RAM. The edits you made to that spreadsheet? Also in RAM. None of it was written back to disk storage until you hit "Save." Modern applications try to help by auto-saving periodically, but they're really just copying data from RAM to disk at regular intervals to protect against data loss.

Size and Speed: The amount of RAM in your computer significantly impacts how well it performs, especially when multitasking. Budget laptops might have 4GB to 8GB of RAM, which is adequate for basic web browsing and document editing. Mid-range computers typically have 16GB, which handles most tasks comfortably, including moderate photo editing and gaming. Power users and professionals might have 32GB or even 64GB for demanding work like video editing, 3D rendering, or running multiple virtual machines.

Servers in data centers can have hundreds of gigabytes of RAM because they need to handle thousands of simultaneous users and keep massive amounts of active data readily accessible.

In terms of speed, RAM is blazingly fast. Modern RAM can transfer data at speeds exceeding 5,000 megabytes per second, with high-end RAM reaching 8,000 MB per second or more. This is significantly faster than even the fastest SSDs, which is exactly the point. The CPU needs data fast, and RAM delivers.

What Happens When You Run Out: When you run out of RAM, your computer doesn't just stop working. Instead, it starts using something called "virtual memory" or a "page file," which is essentially a section of your disk storage that acts as emergency overflow RAM. But remember, disk storage is much slower than RAM, so when your computer starts swapping data between RAM and disk, everything slows down dramatically. This is why opening too many programs at once can make your computer feel sluggish.

Cache: The Speed Demon

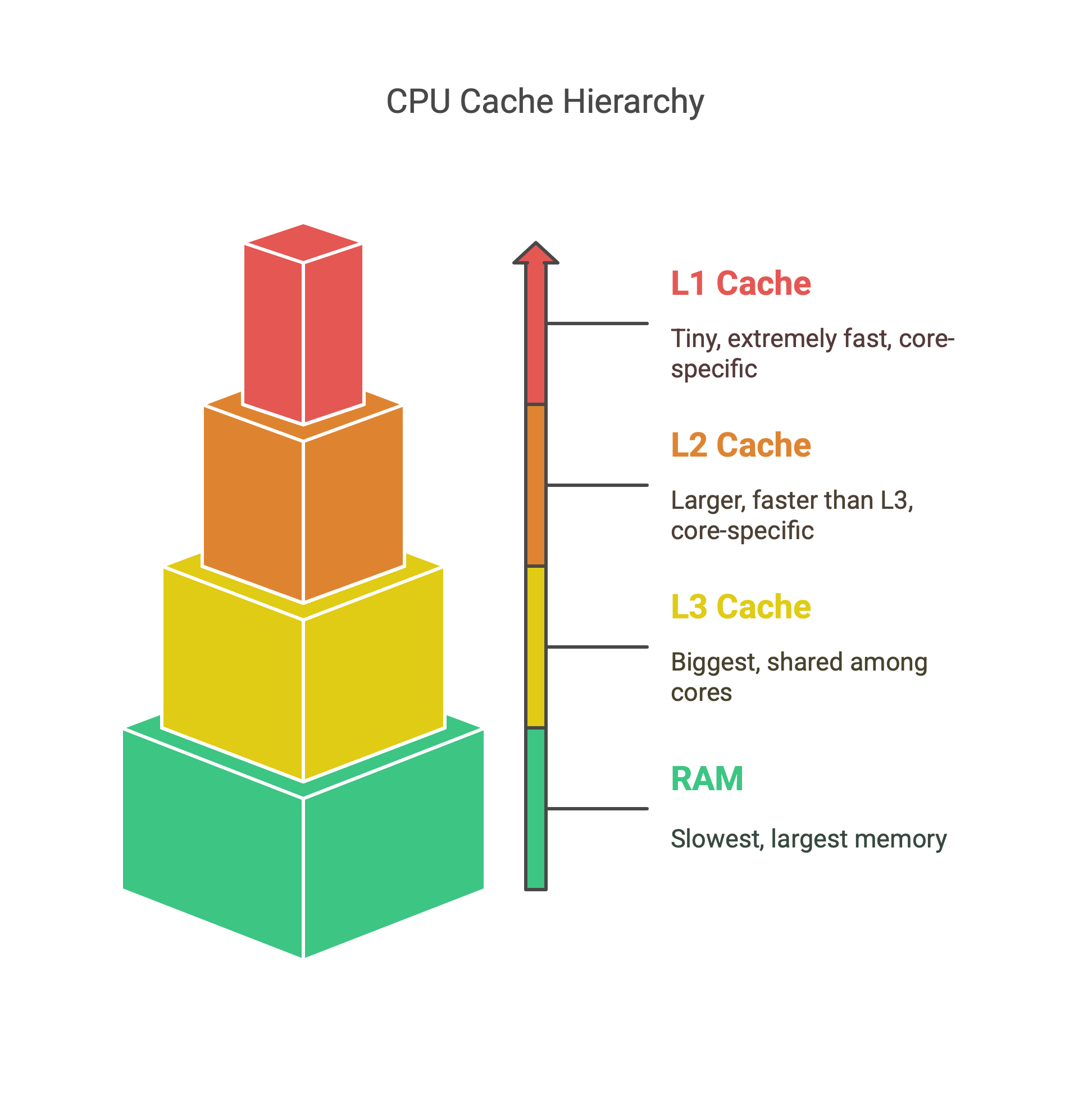

Even with RAM's impressive speed, there's still a problem. The CPU processes billions of operations per second, and even the nanoseconds it takes to fetch data from RAM can become a bottleneck. This is where cache memory comes in, and it's one of the cleverest optimizations in modern computing.

Cache is a small amount of extremely fast memory built directly into the CPU chip itself or located very close to it. We're talking about just a few megabytes of storage, but with access times measured in single-digit nanoseconds. To put this in perspective, if accessing RAM takes 100 nanoseconds, accessing L1 cache might take only 4 or 5 nanoseconds. That might not sound like much, but when your CPU is executing billions of instructions per second, these tiny delays add up.

The Cache Hierarchy: Modern processors don't just have one cache; they have multiple levels, each with different sizes and speeds. This tiered system is designed to balance speed with capacity:

L1 Cache: This is the smallest and fastest cache, typically just 32KB to 128KB per CPU core. It's built right into the core itself and can deliver data to the processor in just a few nanoseconds. The L1 cache is usually split into two parts: one for storing instructions (the actual program code) and one for storing data (the variables and information the program is working with).

L2 Cache: Slightly larger and slightly slower than L1, the L2 cache is usually between 256KB and 1MB per core. It acts as a middle ground between the tiny but lightning-fast L1 and the larger but slower L3. If the CPU can't find what it needs in L1, it checks L2 next.

L3 Cache: This is the largest cache, typically shared among all CPU cores. Modern processors might have anywhere from 8MB to 64MB of L3 cache or even more in server processors. While it's the slowest of the three cache levels, it's still dramatically faster than RAM.

How Cache Works: When the CPU needs a piece of data, it follows a specific search pattern. First, it checks the L1 cache. If the data is there (called a "cache hit"), great! The CPU gets it almost instantly. If not (called a "cache miss"), it checks L2. Still not there? Check L3. If the data isn't in any of the caches, the CPU finally has to fetch it from RAM, which takes much longer.

The beauty of cache is that it works automatically. You don't need to manage it or think about it. The CPU uses sophisticated algorithms to predict which data you're likely to need next and keeps that data in cache. It's constantly shuffling data between the different cache levels and RAM, trying to keep the most frequently accessed information as close to the processing cores as possible.

Why This Matters: Programs typically follow patterns. If you're looping through an array of numbers, the CPU will likely need those numbers in sequence. If you're running a calculation multiple times, the same instructions will be executed repeatedly. Cache takes advantage of these patterns, keeping frequently used data and instructions readily available. This is why processors with larger caches often perform better, especially in tasks that work with the same data repeatedly, like video encoding or scientific simulations.

The CPU: Your Computer's Brain

The Central Processing Unit, or CPU, is where all the action happens. If your computer were a factory, the CPU would be the workers on the assembly line, actually doing the work. Every calculation, every comparison, every decision your computer makes flows through the CPU.

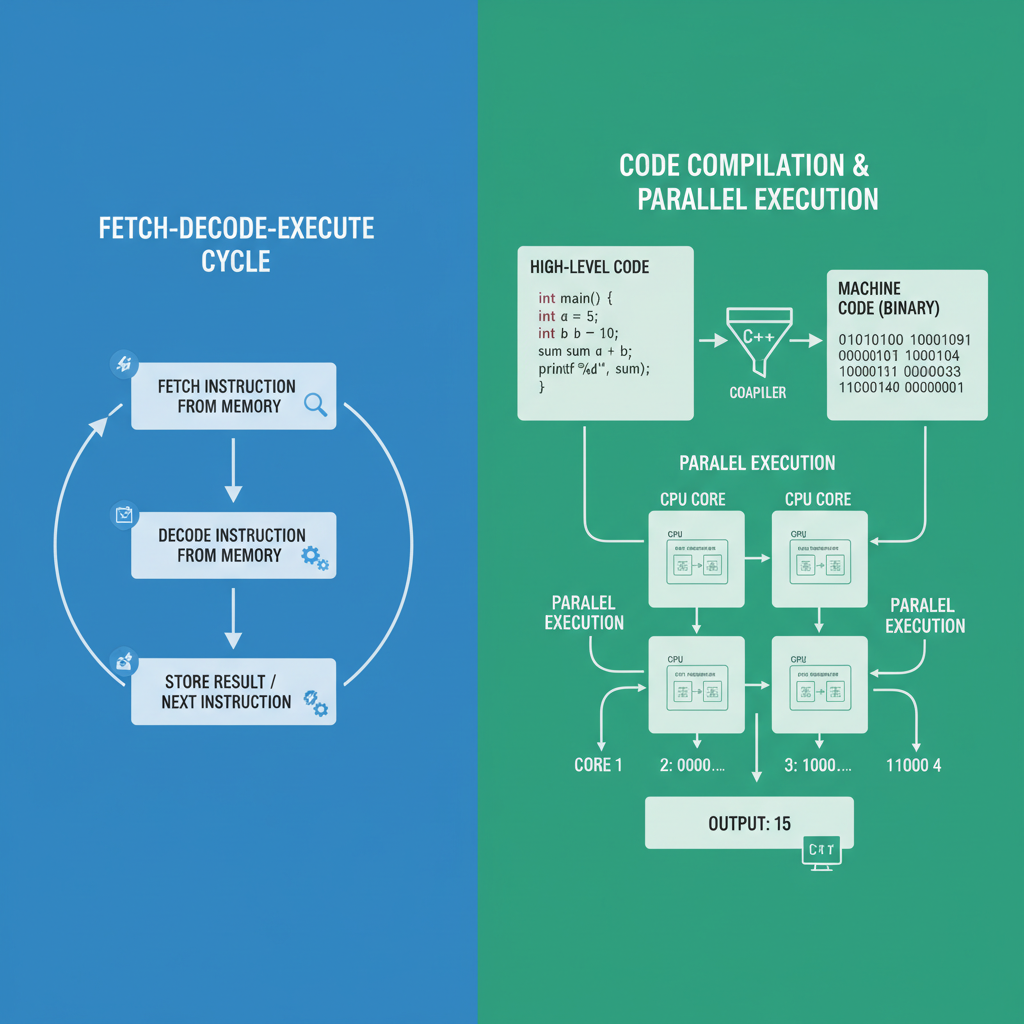

But what exactly does the CPU do? At the most basic level, it performs a continuous cycle of three operations: fetch, decode, and execute.

Fetch: The CPU retrieves an instruction from memory. This instruction is just a number in binary that tells the CPU what to do next.

Decode: The CPU figures out what that instruction means. Does it need to add two numbers? Move data from one place to another? Compare two values?

Execute: The CPU performs the operation. It might do a mathematical calculation, read or write data to memory, or make a decision about what instruction to execute next.

This cycle happens billions of times per second. When you hear that a processor runs at "3.5 GHz," that means it can potentially perform 3.5 billion of these cycles every second (though the actual number of instructions completed is more complex than that).

Multiple Cores: Modern CPUs don't just have one processing unit; they have multiple cores. A "quad-core" processor has four independent processing units that can all work simultaneously. This is like having four workers instead of one. Some tasks can be split up among these cores, allowing your computer to do multiple things truly simultaneously. For example, one core might be rendering a video while another handles your web browser and a third runs a background virus scan.

From Code to Machine Language: Here's something fascinating: the CPU doesn't actually understand the programming languages we use to write software. When a programmer writes code in Python, Java, C++, or any other high-level language, that code is written in a way that's relatively easy for humans to read and understand. But the CPU only understands machine code, which is pure binary instructions.

This is where a compiler or interpreter comes in. A compiler is a special program that reads the human-friendly code and translates it into machine code that the CPU can execute. This translation process happens before the program runs (in compiled languages like C++) or during runtime (in interpreted languages like Python).

For example, when you write something like "x = 5 + 3" in a high-level language, the compiler might translate this into a series of machine code instructions like: "load the value 5 into register 1," "load the value 3 into register 2," "add the contents of register 1 and register 2," and "store the result in the memory location associated with variable x." Each of these steps is a binary instruction that the CPU knows how to execute.

Only after this compilation or interpretation can the CPU actually run your program, reading and writing data from RAM, cache, and disk as needed to accomplish the tasks you've programmed.

The CPU's Connection to Everything: The CPU doesn't work in isolation. It's constantly communicating with all the other components we've discussed. It reads program instructions from RAM, stores frequently used data in its cache, saves results back to RAM, and when needed, writes data to disk for permanent storage. It's the orchestrator of the entire system, directing traffic and making sure every component works together harmoniously.

Modern CPUs are marvels of engineering. They contain billions of transistors packed into a chip smaller than a postage stamp, all working together to execute your instructions with incredible speed and precision.

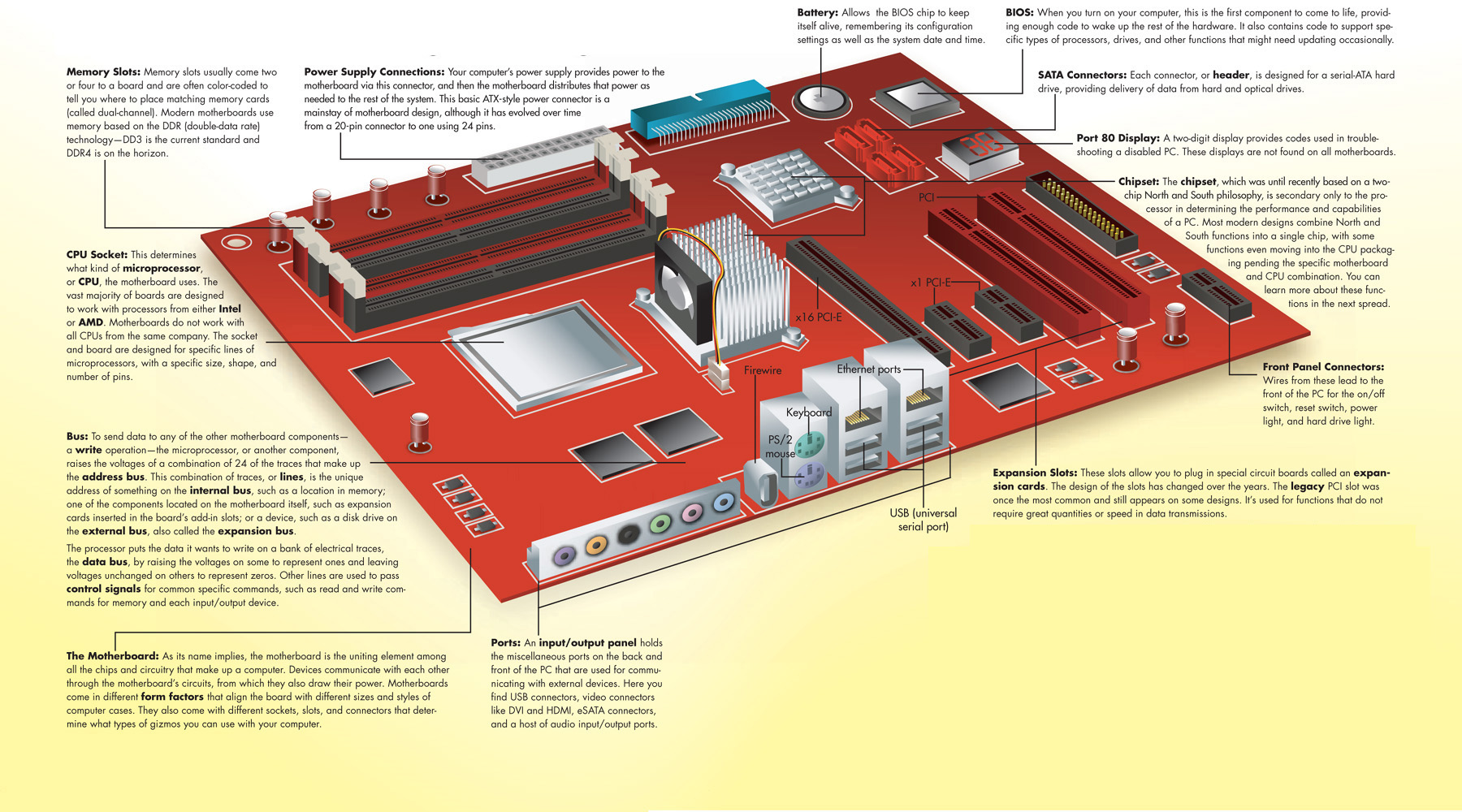

The Motherboard: Connecting It All Together

We've talked about all these individual components, but how do they actually communicate with each other? This is where the motherboard comes in. The motherboard is the large circuit board that everything else connects to, and it's the foundation that makes your computer function as a unified system.

Think of the motherboard as the roads and highways in a city. The CPU, RAM, storage, and all other components are like buildings and neighborhoods. Without the roads connecting them, nothing could move between these locations. The motherboard provides the physical pathways (called buses) that allow data to flow between all the different parts of your computer.

These pathways aren't just simple wires. They're sophisticated communication channels with their own speeds and protocols. The connection between the CPU and RAM needs to be extremely fast because the CPU is constantly pulling data from and writing data to RAM. The connection to your storage drive needs to handle large amounts of data transfer when you're saving files or loading programs. The connection to your graphics card needs to handle massive amounts of visual data if you're gaming or editing video.

The motherboard also houses important chips that manage these communications. The chipset, for example, acts like a traffic controller, directing data along the most efficient paths and ensuring that everything arrives where it needs to go. It manages things like USB ports, audio connections, network adapters, and more.

Additionally, the motherboard provides power distribution to all the components, ensuring that everything gets the electricity it needs to function properly.

Putting It All Together: A Real-World Example

Let's walk through what actually happens when you click on a program icon to help you see how all these components work together.

Step 1: You click on an application icon. This action generates an interrupt that tells the CPU "hey, the user wants to do something."

Step 2: The CPU looks up where that program's files are stored on disk. This information is usually cached in RAM or even in the CPU's cache if you've opened this program recently.

Step 3: The CPU instructs the disk controller to read the program files from disk storage. If you have an SSD, this happens very quickly. If you have an HDD, you might hear it spin up and click as the read head moves into position.

Step 4: The program data is copied from disk into RAM. Depending on the size of the program, this might be a few megabytes to hundreds of megabytes.

Step 5: The CPU starts executing the program's instructions, which are now in RAM. As it works, it keeps frequently accessed instructions and data in its cache for even faster access.

Step 6: The program might create windows, load additional resources, and set up its working environment, all of which involves more reading from disk and storing in RAM.

Step 7: As you use the program, the CPU constantly fetches instructions from RAM, performs calculations, and updates the display. Frequently used data moves into cache, and less-used data might be swapped out to make room.

Step 8: When you save your work, the CPU writes data from RAM back to disk storage, where it's permanently recorded.

This entire process, from click to seeing the application window, might take just a few seconds, but it involves millions of individual operations coordinated across all your computer's components.

Why Understanding This Matters

You might wonder why any of this matters if you're not a computer engineer. Understanding computer architecture helps you make better decisions about your technology and troubleshoot problems when they arise.

When shopping for a new computer, knowing what these components do helps you choose the right specifications. If you mainly browse the web and work with documents, you don't need massive amounts of RAM or the fastest CPU. But if you edit videos or play demanding games, you'll want more RAM, a faster processor, and definitely an SSD.

When your computer runs slowly, understanding architecture helps you diagnose the problem. Is everything slow, including boot time? You might need an SSD. Do programs run fine individually but everything slows down when you have many open? You probably need more RAM. Are specific tasks like video rendering or photo editing sluggish? A faster CPU might help.

You'll also understand why certain upgrades make sense and others don't. Adding more RAM to a computer that's constantly running out makes a huge difference. Adding more RAM to a computer that's only using half of what it has won't do anything. Upgrading from an HDD to an SSD transforms the user experience. Upgrading from one SSD to a slightly faster SSD might not be noticeable in daily use.

The Ever-Evolving Landscape

Computer architecture isn't static. Engineers are constantly finding ways to make processors faster, memory larger and quicker, and storage more capacious and speedy. Just a few years ago, 4GB of RAM was considered plenty for most users. Today, 8GB is the minimum, and 16GB is becoming standard.

SSDs were once exotic and expensive. Now they're common in even budget laptops. Cache sizes have grown, CPU core counts have increased, and new technologies continue to emerge.

But despite all this evolution, the fundamental principles we've discussed remain the foundation of computing. Programs are compiled into machine code, the CPU executes instructions, active data lives in RAM, frequently used data gets cached, and permanent storage sits on disk. Understanding these basics gives you a mental model that will remain relevant even as the specific technologies continue to improve.

The next time you sit down at your computer, take a moment to appreciate the incredible engineering that makes it all work. Every click, every keystroke, every pixel on your screen is the result of these components working together in perfect harmony, processing billions of operations every second to make your digital life possible.